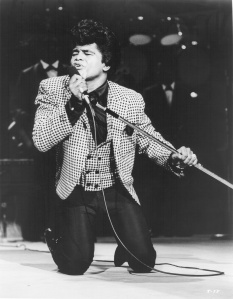

The debut on August 1, 2014 of the James Brown biopic “Get On Up” starring Chadwick Boseman, Jill Scott, and Viola Davis, allows hard core James Brown fans like myself a chance to reassess his legacy. When the Godfather passed in 2006, there was a suitable outpouring of emotion represented by his tributes at the Apollo Theater and at James Brown Auditorium in Augusta, Georgia. Yet, Brown had survived Otis Redding, Miles Davis, Elvis Presley, John Coltrane, Marvin Gaye, Little Willie John, Janis Joplin, John Lennon, and many other artists of his generation who were essential in providing a musical soundtrack for the social changes that took place in the latter half of the 20th Century. Because of his longevity and the massive reach of his impact, Mr. Brown became someone one could almost take for granted.

The true appreciation of Mr. Brown for me began early, but still somewhat later than it should have. As an ’80s baby, I grew up with The Godfathers descendants such as Prince, and Michael Jackson. The large funk bands were generally seen as on the decline, excepting Cameo, The Gap Band, and survivors like Kool & The Gang and The (Lionel Ritchie less) Commodores. Groups like New Edition had the youth audience. New soul flavors were coming over from the United Kingdom. My parents were huge James Brown fans but they were also musical progressives. In the home I was hearing a lot of Grover Washington Jr, Miles Davis, Sade, Luther Vandross, Whitney Houston, George Benson, recent late ’70s Commodores, Herbie Hancock electric funk, Steps Ahead, and a whole lot of Reggae. My older brothers and sisters were playing Prince and Hip Hop, plus great ’80s singles like “Hangin On a String” by Loose Ends. On lazy Saturdays or Sundays Dad would break out the reel to reel machine and play Coltrane, Herbie Mann, Stan Getz, old Miles Davis, Eddie Harris, Billie Holliday, Duke Ellington, Sonny Rollins, Louis Armstrong, Diz and Bird, and many programs he D.J’ed for VOA’s “Sound of Jazz” program.

Somehow in all of this, I only saw and heard fleeting glimpses of James Brown. Of course, J.B was very busy at this time, recording “Unity” with Afrika Baambaata, having one of his biggest pop hits ever in “Living in America”, touring all around the world, and eventually, getting into trouble. But somehow, in Oakland, California, a city that had been finally taken over politically by its black majority, and which had always been a key stop on the James Brown Express, I didn’t actually hear too much J.B in my earliest years.

All of this seemed to change around 1987, 1988, which is right when Hip Hop reasserted James Brown’s influence on both their music and the culture. The early Hip Hop D.J’s in New York used all manner of James Brown tunes to rock their parties. What sometimes gets lost is, many of these James Brown songs were contemporaneous to the early hip hop parties. For instance, in 1974 when the first Hip Hop parties were held, James Brown had singles such as “The Payback”, “Doin it to Death”, and “Funky President.” He also rocked the concert in Zaire (now the Congo) that went along with the Muhammed Ali, George Foreman title fight known as “The Rumble in the Jungle”, of which this year is the 40th anniversary. James pop profile dimminished each year after that, but he still had thunderous hits like 1976’s “Get Up Offa That Thang” (which provided the horn blasts for Boogie Down Production’s classic “South Bronx”). He was a fixture on the R&B charts even in the late ’70s, as viewings of ’70s episodes of Soul Train will attest to. Records like “The Spank”, “For Goodness Sakes Take a Look at Those Cakes”, “Eyesight”, “A Man Understands”, “Bodyheat” and “Give Me Some Skin”. These records captured the essence of the J.B groove in the high point of the great funk bands such as EWF, Parliament-Funkadelic, The Commodores, Kool & The Gang, The Isley Brothers, Sly & The Family Stone, Graham Central Station, and many other funky artists in that funky decade. A glance at Soul Train episodes post 1975 will show you how whether a song went to the top of the charts or not, James Brown funk always did what it was designed to do, get people up!

Of course, around 1988-1989 Mr. Brown came into my attention for the troubles he was having with the law at that time. I’d seen him earlier do his cape routine on the special, “Motown Goes Back to the Apollo.” It was kind of hard to seperate James Brown, his impact, and how his music still related to the modern thing, when he was placed alongside his peers and rock and roll legends such as Little Richard, Lloyd Price, and the Four Tops. All of these artists were great, influnetial artists, but their music and social impacts were not about to reignite like Mr. Brown’s was, in the late ’80s.

I remember watching Entertainment Tonight with my mom and seeing Mr. Brown going to jail and her talking about “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud”, and James Browns concert in Monrovia, Liberia, and how she loved his hair. My dad talked about James Brown and the J.B’s and his favorite songs, like “You Can Have Watergate (But Gimmie Some Bucks and I’ll be straight), and “There Was a Time” with it’s “Groove Maker”, and “Doin it to Death”, and J.B’s career as an organist on Smash records.

Then, my real immersion into hip hop began. Earlier Hip Hop in the ’80s had used drum machines to contstruct spare, original beats, inspired by older funk and rock, but not directly sampling the recordings. By the late ’80s it seemed the world was a constant barrage of raw, James Brown beats. On every side of hip hop I liked, JB was there, from Eric B and Rakim’s “I Know You Got Soul” and “I Aint No Joke”, to Salt & Pepa hollering “Pick up on this”, from Kool Moe Dee’s “I Go to Work”, to The 45 King’s “900 Number.”

My primary two influnces in hip hop, disparate as they were, both trafficed in James Brown. Public Enemy and M.C Hammer covered different sides of the man’s music and legacy. Public Enemy sampled bits and pieces of many recordings to create their own new funk. Chuck D and Flavor Flav traded off vocals in the manner of James Brown and Bobby Byrd. Their music focused on street conditions and black empowerment, just as Mr. Brown did on “Dont Be a Dropout”, “I Don’t Want Nobody to Give Me Nothing”, “Mind Power”, “Get Up, Get Into it, Get Involved”, “Soul Power”, “Funky President”, “Reality”, and many other songs. The controversy they generated at times in their career could call to mind the social currency James Brown had, the way he was black listed after “Say it Loud” for instance.

M.C Hammer, my Oakland hometown hero, represented another side of James Brown legacy. While Public Enemy were consumate performers as well, Hammer actually was a dancing machine, with a large band, back up dancers, and the theatrical presentation that Mr. Brown and other soul era performers bought. He also was largely successfull and admired for his business acumen, as Mr. Brown was in his day, when he was known for owning 4 radio stations and a Lear Jet. Hammer built on and expanded on the R&B influenced side of Hip Hop performing, represented over the years by Afrika Baambaata, Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, Whodini, and Kool Moe Dee. This style has pretty much always lost out in hip hop to the spare RUN DMC style of M.C’s walking back and forth across the stage, which some people feel is more pure and reflective of Hip Hop’s New York City park origins. But there are always people like Hammer who bring the R&B glitter and excitement to their performances as well. Hammer though, was the best and the most compelling.

Hammer also represented the other side of James Browns social concern. If Public Enemy was pegged as the radical side, Hammer represented the side that was about stopping the violence in the urban neighborhoods, getting an education, going to work, owning businesses, and building. Of course, in a post Civil Rights, post Black Power world, Hammer, who was from the city of the Black Panthers, had a millitant side too, but that is not what people saw. Hammers insistence on not cursing because he was a role model for kids was also from the James Brown book. Together, Public Enemy and Hammer represented all those sides of J.B.

But Browns impact was not limited to them. Somehow, as a little kid in the ’80s I didn’t know Michael Jackson and Prince were descendants of J.B as well, maybe the TOP two. M.J maybe took James Browns performance based ethic to it’s highest height, and Prince expanded on his role as a musical innovator of funk, by also incorporating the innovations of Brown’s contemporaries, like Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Little Richard, The Rolling Stones, P-Funk, Al Green, and many others. But M.J and Prince were able to inhabit a whole other rarified air for black pop stars, delivering music that was authentic and yet widely popular at the same time. But somehow, it would take much later for me to understand the high tech, futuristic funky pop of The Thriller and His Royal Badness as fruits from the James Brown root.

Arsenio Hall’s show was key in exposing me to James Browns performances. I remember pestering my Dad about Brown, and pops breaking out the vinyl to “Live At the Apollo Vol 2” and “Doin it to Death”. He laughed as he recounted stories of Richard Nixon and Watergate. And he told me about a huge audience in Monrovia, Liberia singing along to “Hey, Hey, I Feel all Right.”

My appreciation for Mr. Brown would grow throughout the ’90s, as I purchased CD compilations and eventually vinyl albums. A James Brown concert was even my first concert ever, at the Paramount Theater in Oakland, California, with my parents and my best friends, Jesse and Frank. The appreciation of Mr. Brown has been something I’ve bonded with over many people, and his determination, drive, attention to appearance, independence, pride and many other aspects of the man continue to inspire me to this day.

This series will cover various aspects of James Brown’s music and career in anticipation of the August 1 release of the “Get on Up” movie. It will continue to run for the duration of the summer, which will take us into around October on the West Coast. James Brown’s funk music is very direct and does not take much thought to get into. But James Brown’s life, career, impact, and the specific messages he put out there are very rich subjects that point to a very unique viewpoint on America, Black people in America, and the world. James Brown was a poor sharecropers son who grew up in a Whorehouse and was a Juevenile Delinquent, who rose from that to become one of the most impactful, classiest entertainers of all time. As such, he had a unique message to share. And he was never one of those singers who felt they should “just sing.” Brown was unique because although his show definitely provided escapism, through its funky grooves, slick outfits and large dynamics, it was an escapism of, or through IMMERSION. James Brown, in that fine Black tradition, immersed you in reality, and sometimes troubles, to get you to go past and transcend them. Or as he would say, “Get Up offa that thang, and dance till you feel better!” As Chadwick Boseman brings him to life across the celluloid screen, now is as fine a time as ever to look at a portion of what Mr. Brown did and how he did it.